You step on the scale, check your reflection in the mirror, and feel satisfied with what you see. Your BMI falls within the normal range, you exercise regularly, and outwardly, you appear to be the picture of health. But what if I told you that hidden deep within your body, an invisible type of fat could be silently wreaking havoc on your cardiovascular system?

This hidden culprit is called visceral fat, and unlike the subcutaneous fat you can pinch on your arms or thighs, it lurks around your internal organs where you can’t see or feel it. Recent scientific research has revealed that this invisible fat may be one of the most dangerous threats to your heart health—even if you maintain a regular exercise routine and appear physically fit.

The Tale of Two Fats: Understanding Your Body’s Fat Storage System

To understand why some fat is more dangerous than others, we need to explore how your body stores and uses fat. Not all fat is created equal, and the location where fat accumulates in your body can mean the difference between metabolic health and cardiovascular disease.

Subcutaneous Fat: The Visible Layer

Subcutaneous fat is the soft, pinchable fat that sits just beneath your skin. This is the fat you can see in the mirror—it creates the curves of your hips, the softness of your arms, and the layer over your abdominal muscles. From an evolutionary perspective, subcutaneous fat serves several important functions:

Advantages of Subcutaneous Fat:

- Insulation: Acts as a thermal barrier, helping regulate body temperature

- Energy storage: Provides a readily available fuel source during times of food scarcity

- Cushioning: Protects bones and muscles from impact and injury

- Hormone production: Produces leptin, which helps regulate appetite and metabolism

- Metabolic buffer: Can safely store excess energy without immediate health consequences

Disadvantages of Excessive Subcutaneous Fat:

- Can contribute to insulin resistance when present in very large amounts

- May cause joint stress and mobility issues

- Can impact self-esteem and body image

- Associated with increased inflammation when excessive

Research published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation has shown that subcutaneous fat, particularly in the hip and thigh regions, may actually be protective against metabolic disease. This “pear-shaped” fat distribution appears to act as a metabolic sink, safely storing excess energy away from vital organs.

Visceral Fat: The Hidden Danger

Visceral fat, also known as intra-abdominal fat, accumulates around your internal organs including your liver, pancreas, and intestines. Unlike subcutaneous fat, you can’t see or feel visceral fat, making it a silent threat to your health.

The Limited Advantages of Visceral Fat:

- Organ protection: In small amounts, provides cushioning for internal organs

- Quick energy access: Can be rapidly mobilized during times of acute stress or energy need

The Significant Disadvantages of Excess Visceral Fat:

- Inflammatory factory: Produces pro-inflammatory cytokines that promote chronic inflammation

- Insulin resistance: Interferes with insulin signaling, leading to elevated blood sugar

- Hormone disruption: Produces hormones that can disrupt normal metabolic processes

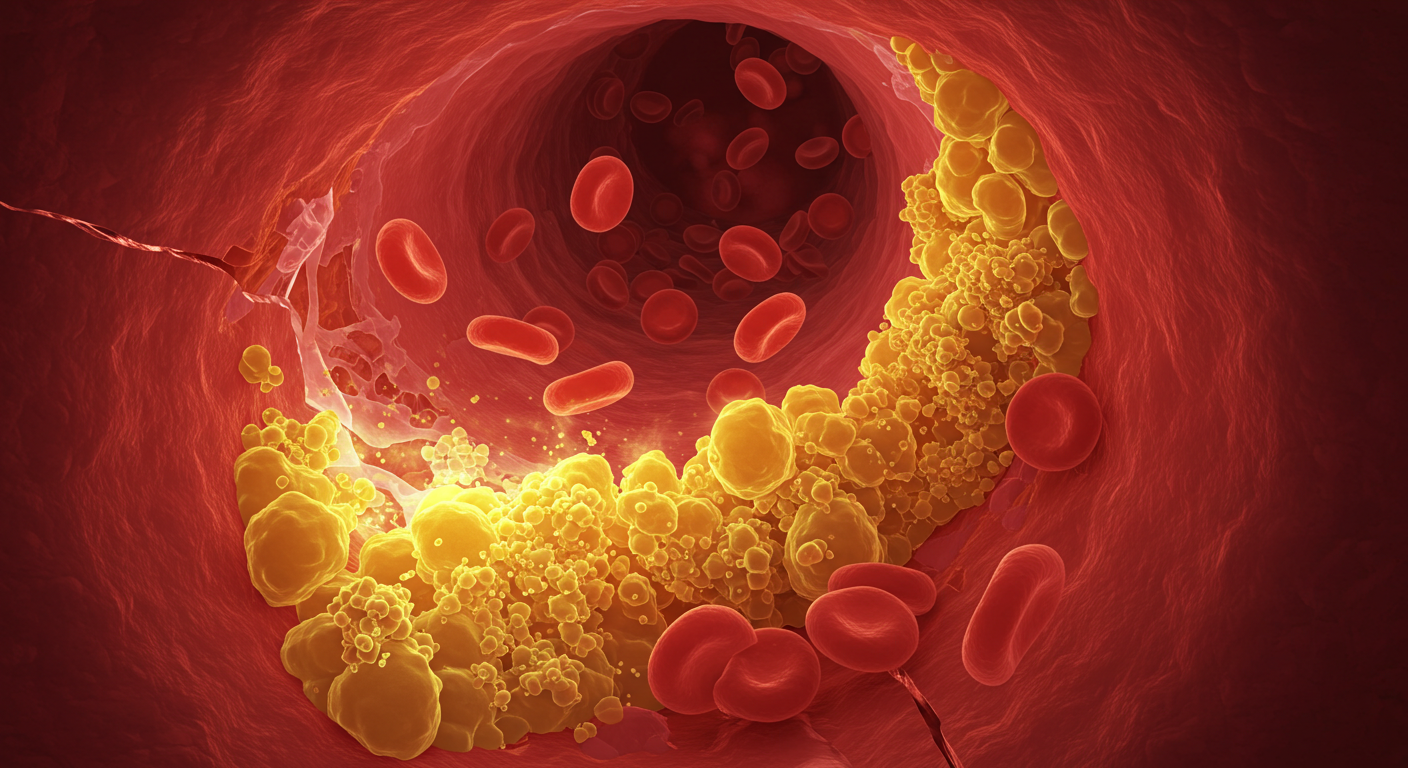

- Cardiovascular risk: Directly contributes to atherosclerosis and heart disease

- Liver dysfunction: Can lead to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Cancer risk: Associated with increased risk of several types of cancer

A landmark study published in the New England Journal of Medicine followed over 350,000 participants for nearly 10 years and found that individuals with excess visceral fat had a significantly higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease, even when their overall weight was normal.

The Science Behind Visceral Fat and Heart Disease

Understanding why visceral fat is so dangerous requires delving into the molecular mechanisms by which this tissue affects your cardiovascular system. Unlike passive subcutaneous fat, visceral fat is metabolically active, essentially functioning as an endocrine organ that pumps out a cocktail of harmful substances.

The Inflammatory Connection

Visceral fat cells, known as visceral adipocytes, are larger and more inflammatory than their subcutaneous counterparts. Research published in Circulation Research has shown that visceral fat produces significantly higher levels of inflammatory markers, including:

- Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α): Promotes insulin resistance and atherosclerosis

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6): Increases systemic inflammation and cardiovascular risk

- C-reactive protein (CRP): A marker of inflammation strongly linked to heart disease

- Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1): Increases blood clotting risk

These inflammatory molecules don’t stay localized around your organs—they enter your bloodstream and travel throughout your body, creating a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation that accelerates atherosclerosis (the buildup of plaque in your arteries).

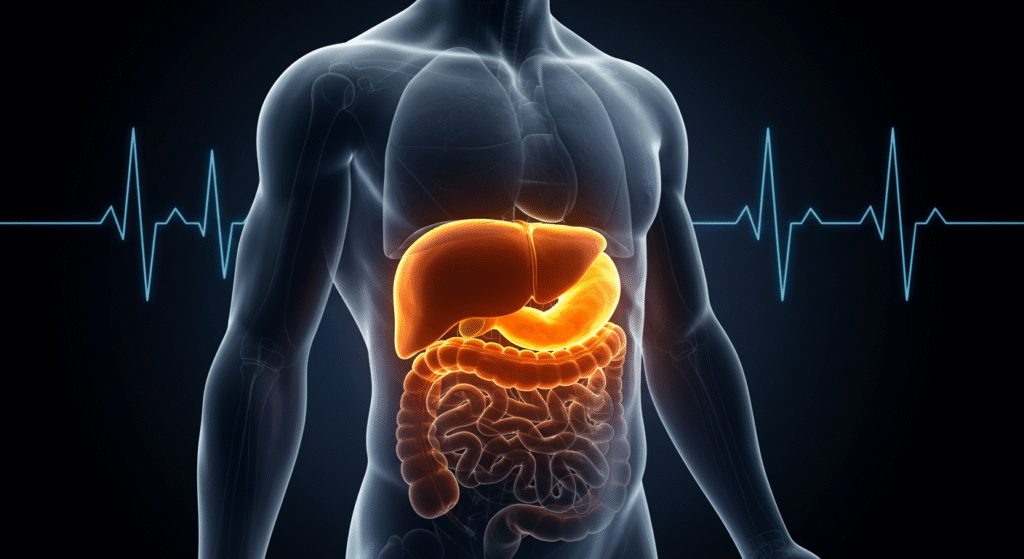

The Portal Circulation Problem

One of the most concerning aspects of visceral fat is its anatomical location. The blood that drains from visceral fat flows directly to your liver through the portal circulation system. This means that all the toxic substances produced by visceral fat—including free fatty acids and inflammatory molecules—are delivered in high concentrations directly to your liver.

This direct delivery system leads to several problems:

- Hepatic insulin resistance: The liver becomes less responsive to insulin

- Increased glucose production: The liver produces more glucose, raising blood sugar

- Altered lipid metabolism: The liver produces more harmful LDL cholesterol and triglycerides

- Fatty liver disease: Excess fat accumulation in liver cells

The Insulin Resistance Cascade

Visceral fat is a major driver of insulin resistance, a condition where your cells become less responsive to insulin’s effects. A study in Diabetes Care demonstrated that visceral fat is more strongly associated with insulin resistance than total body fat or subcutaneous fat.

When insulin resistance develops, several cardiovascular risk factors emerge:

- Elevated blood glucose: Leads to glycation of proteins and oxidative stress

- High triglycerides: Contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation

- Low HDL cholesterol: Reduces the body’s ability to clear harmful cholesterol

- High blood pressure: Results from various metabolic disturbances

- Increased clotting tendency: Raises risk of heart attack and stroke

The Exercise Paradox: Why Working Out Isn’t Always Enough

Here’s where the story becomes particularly concerning for health-conscious individuals. You might assume that regular exercise would protect you from visceral fat accumulation and its associated risks. While exercise is undoubtedly beneficial and can help reduce visceral fat, it’s not a guarantee of protection, especially if other factors are working against you.

The Limitations of Exercise in Visceral Fat Reduction

Research published in the Journal of Applied Physiology has shown that while exercise can reduce visceral fat, the response is highly variable among individuals. Several factors influence how effectively exercise can combat visceral fat:

Genetic Factors: Some people are genetically predisposed to store fat viscerally rather than subcutaneously. Studies of identical twins have shown that genetic factors account for approximately 50-60% of the variation in visceral fat accumulation.

Age-Related Changes: As we age, hormonal changes—particularly decreases in growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen—promote the preferential storage of fat in the visceral compartment. Even regular exercisers experience some age-related increase in visceral fat.

Stress and Cortisol: Chronic stress leads to elevated cortisol levels, which preferentially promote visceral fat storage. The stress of modern life can counteract some of the benefits of exercise, particularly if stress management isn’t prioritized.

Sleep Quality: Poor sleep quality and insufficient sleep duration are associated with increased visceral fat accumulation. Research in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that people who slept less than 6 hours per night had significantly more visceral fat than those who slept 7-8 hours.

Dietary Factors: Exercise can’t completely overcome a poor diet. Diets high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and trans fats promote visceral fat accumulation even in active individuals.

The “Skinny Fat” Phenomenon

Perhaps most concerning is the phenomenon of “skinny fat” or normal weight obesity. These individuals maintain a normal BMI and may exercise regularly, but they have a high percentage of body fat, much of it stored viscerally.

A study in the European Heart Journal followed over 40,000 women for 16 years and found that those with normal BMI but excess abdominal fat had a nearly 40% higher risk of cardiovascular death compared to those with healthy fat distribution, even when accounting for exercise levels.

Detecting the Invisible Enemy: How to Measure Visceral Fat

Since visceral fat can’t be seen or felt, detecting it requires specific measurement techniques. Understanding these methods can help you assess your own risk and monitor progress if you’re working to reduce visceral fat.

Waist Circumference: The Simple Screening Tool

The most accessible method for assessing visceral fat is measuring your waist circumference. Research has shown that waist circumference correlates strongly with visceral fat levels and cardiovascular risk.

Risk Thresholds:

- Men: Waist circumference > 40 inches (102 cm) indicates increased risk

- Women: Waist circumference > 35 inches (88 cm) indicates increased risk

Proper Measurement Technique:

- Use a flexible measuring tape

- Measure at the narrowest point between your ribs and hip bones

- Measure while standing, after breathing out normally

- Don’t suck in your stomach or pull the tape too tight

Waist-to-Hip Ratio: Refining the Assessment

The waist-to-hip ratio provides additional information about fat distribution patterns. This measurement compares your waist circumference to your hip circumference (measured at the widest part of your hips).

Risk Thresholds:

- Men: Ratio > 0.90 indicates increased risk

- Women: Ratio > 0.85 indicates increased risk

Advanced Imaging Techniques

For the most accurate assessment of visceral fat, advanced imaging techniques are available:

DEXA Scan (Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry): Provides detailed body composition analysis, including visceral fat estimation. Widely available and relatively affordable.

CT or MRI Imaging: The gold standard for visceral fat measurement. These techniques can precisely quantify visceral fat volume but are expensive and typically reserved for research or high-risk patients.

Bioelectrical Impedance: Some advanced scales and devices can estimate visceral fat levels using bioelectrical impedance. While convenient, these measurements can be less accurate than other methods.

The Comprehensive Strategy: Targeting Visceral Fat for Heart Health

Now that you understand the dangers of visceral fat, let’s explore evidence-based strategies for reducing it and protecting your cardiovascular health.

Exercise Strategies That Work

While exercise alone may not be sufficient, specific types of exercise are particularly effective at reducing visceral fat:

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): Research published in Obesity Reviews found that HIIT is superior to steady-state cardio for reducing visceral fat. HIIT sessions involving short bursts of intense activity followed by recovery periods appear to preferentially target abdominal fat.

Resistance Training: Strength training helps build muscle mass, which increases metabolic rate and improves insulin sensitivity. Studies show that combining resistance training with cardio is more effective than either alone for reducing visceral fat.

Consistent Moderate Exercise: While high-intensity exercise gets attention, consistent moderate exercise (like brisk walking for 150 minutes per week) has proven benefits for reducing visceral fat and improving cardiovascular health.

Nutritional Approaches

Diet plays a crucial role in visceral fat accumulation and reduction:

Reduce Refined Carbohydrates: Studies consistently show that diets high in refined carbs and added sugars promote visceral fat storage. Focus on whole grains, vegetables, and fruits instead.

Increase Protein Intake: Higher protein intake (0.8-1.2 grams per kilogram of body weight) helps preserve muscle mass during weight loss and improves satiety.

Choose Healthy Fats: Replace trans fats and excessive saturated fats with monounsaturated and omega-3 fatty acids found in olive oil, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish.

Control Portion Sizes: Even healthy foods can contribute to visceral fat accumulation if consumed in excess. Practice portion control and mindful eating.

Stress Management

Chronic stress promotes visceral fat accumulation through elevated cortisol levels. Effective stress management strategies include:

- Regular meditation or mindfulness practice

- Adequate sleep (7-9 hours per night)

- Social connection and support

- Time management and work-life balance

- Professional counseling when needed

Sleep Optimization

Quality sleep is crucial for healthy fat distribution:

- Maintain consistent sleep and wake times

- Create a dark, cool sleeping environment

- Limit screen time before bed

- Avoid caffeine and large meals close to bedtime

- Consider sleep disorders evaluation if you have persistent sleep problems

The Hormonal Connection: Age, Gender, and Visceral Fat

Understanding how hormones influence visceral fat accumulation helps explain why this type of fat becomes more problematic with age and differs between men and women.

Women and Menopause

Before menopause, estrogen helps promote subcutaneous fat storage in the hips and thighs while limiting visceral fat accumulation. However, during and after menopause, declining estrogen levels lead to a shift toward visceral fat storage.

Research in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism found that postmenopausal women have significantly more visceral fat than premenopausal women, even when total body weight remains constant. This hormonal shift helps explain why cardiovascular disease risk increases dramatically in women after menopause.

Men and Testosterone

Men naturally tend to store more fat viscerally than women, but this tendency increases with age as testosterone levels decline. Low testosterone is associated with increased visceral fat, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular risk.

Studies have shown that testosterone replacement therapy in men with clinically low levels can help reduce visceral fat and improve cardiovascular risk factors, though this treatment requires careful medical supervision.

The Growth Hormone Connection

Growth hormone (GH) plays a crucial role in fat distribution, and GH levels decline with age in both men and women. Lower GH levels are associated with increased visceral fat accumulation and cardiovascular risk.

While GH replacement therapy exists, it’s expensive and has potential side effects. Natural ways to support healthy GH levels include getting adequate sleep, regular exercise (particularly resistance training), and maintaining a healthy body composition.

Looking Forward: The Future of Visceral Fat Research

Scientific understanding of visceral fat and its health impacts continues to evolve. Emerging research areas include:

Personalized Medicine: Genetic testing may soon help identify individuals at highest risk for visceral fat accumulation, allowing for targeted prevention strategies.

Novel Therapeutics: Researchers are developing medications that specifically target visceral fat or its harmful effects, though these are still in experimental stages.

Microbiome Connections: Growing evidence suggests that gut bacteria influence visceral fat accumulation and inflammation, opening new avenues for intervention through probiotics and dietary modifications.

Advanced Imaging: New imaging techniques may make visceral fat assessment more accessible and affordable, allowing for better monitoring and prevention.

Conclusion: Taking Action Against the Invisible Threat

The fat you can’t see may indeed be damaging your heart, even if you exercise regularly and appear healthy on the outside. Visceral fat represents a hidden but significant threat to cardiovascular health through its promotion of inflammation, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction.

However, this isn’t a cause for despair—it’s a call to action. By understanding the unique dangers of visceral fat and implementing comprehensive strategies that go beyond exercise alone, you can protect your heart health and reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease.

The key is recognizing that optimal health requires attention to multiple factors: regular physical activity, stress management, quality sleep, and a nutritious diet all work together to combat visceral fat accumulation. While exercise is crucial, it’s most effective as part of a holistic approach to health.

Remember that small changes can make a big difference. Even a modest reduction in visceral fat can significantly improve your cardiovascular risk profile. The invisible fat around your organs may be hidden from view, but with the right knowledge and strategies, it doesn’t have to remain hidden from your control.

Start by measuring your waist circumference today. If it’s above the recommended thresholds, consider it a wake-up call to take action. Your heart—and your future self—will thank you for addressing this invisible threat before it causes visible damage.

The science is clear: the fat you can’t see matters more than you might think. But armed with knowledge and commitment to comprehensive health strategies, you can win the battle against this hidden enemy and protect your cardiovascular health for years to come.

Sources and Further Reading:

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “The Nutrition Source: Fats and Cholesterol.”

Neeland, I. J., et al. (2019). “Associations of Visceral and Abdominal Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue with Markers of Cardiac and Metabolic Risk in Obese Adults.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 73(15), 1860-1872.

Tchernof, A., & Després, J. P. (2013). “Pathophysiology of Human Visceral Obesity: An Update.” Physiological Reviews, 93(1), 359-404.

Mozaffarian, D., et al. (2006). “Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine, 354(15), 1601-1613.

Hairston, K. G., et al. (2012). “Lifestyle Factors and 5-Year Abdominal Fat Accumulation in a Minority Cohort: The IRAS Family Study.” Obesity, 20(2), 421-427.